Scientists believe the stellar body was born from the same gas cloud as our own sun (pictured). The researchers claim there is a 'small' chance that this solar sibling could host planets that harbour life

Astronomers believe they have found the sun’s ‘long-lost brother’ – a stellar body born from the same gas cloud as our own star. The researchers claim there is even a ‘small’ chance that this solar sibling could host planets that harbour life. But even if its solar system proves barren, the discovery could help scientists find other stellar twins and may help shed light on how our sun formed.

The University of Texas says the star, called HD 162826, is 15 per cent more massive than our sun and located 110 light-years away in the constellation Hercules. The star is not visible to the unaided eye, but easily can be seen with low-power binoculars, not far from the bright star Vega

WHERE IS OUR SOLAR SIBLING?

The sun’s ‘long-lost brother' is a star called HD 162826.

It is a star 15 per cent more massive than the sun, located 110 light-years away in the constellation Hercules. The star is not visible to the unaided eye, but can be seen with low-power binoculars, not far from the bright star Vega.

It is a star 15 per cent more massive than the sun, located 110 light-years away in the constellation Hercules. The star is not visible to the unaided eye, but can be seen with low-power binoculars, not far from the bright star Vega.

‘If we can figure out in what part of the galaxy the sun formed, we can constrain conditions on the early solar system. That could help us understand why we are here.’

In their earliest days, collisions could have knocked chunks off of planets, and these fragments could have travelled between solar systems. These may have been responsible for bringing primitive life to Earth. Or, fragments from Earth could have transported life to planets orbiting solar siblings.

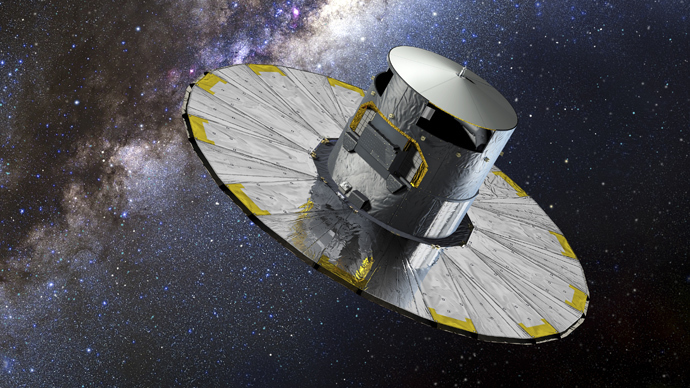

GAIA:

Gaia is a powerful satellite telescope

Gaia’s goal is to create the most accurate map yet of the Milky Way. It will make precise measurements of the positions and motions of about 1% of the total population of roughly 100 billion stars in our home Galaxy to help answer questions about its origin and evolution.

Repeatedly scanning the sky, Gaia will observe each of its billion stars an average of 70 times each over five years. In addition to positions and motions, Gaia will also measure key physical properties of each star, including its brightness, temperature and chemical composition.

Eventually, the Gaia data archive will exceed a million Gigabytes, equivalent to about 200 000 DVDs of data.

Repeatedly scanning the sky, Gaia will observe each of its billion stars an average of 70 times each over five years. In addition to positions and motions, Gaia will also measure key physical properties of each star, including its brightness, temperature and chemical composition.

Eventually, the Gaia data archive will exceed a million Gigabytes, equivalent to about 200 000 DVDs of data.

The solar sibling star his team identified is not visible to the unaided eye, but easily can be seen with low-power binoculars, not far from the bright star Vega. While the finding of a single solar sibling is intriguing, Professor Ramirez points out that the project has a larger purpose: to create a road map for how to identify solar siblings, in preparation for the flood of data expected soon from surveys like Gaia.

‘The idea is that the sun was born in a cluster with a thousand or a hundred thousand stars. This cluster, which formed more than 4.5 billion years ago, has since broken up,’ he said.

The member stars have broken off into their own orbits around the galactic center, taking them to different parts of the Milky Way today. A few, like HD 162826, are still nearby. Others are much farther afield.

The data coming soon from Gaia is ‘not going to be limited to the solar neighborhood,’ Professor Ramirez said.

‘The number of stars that we can study will increase by a factor of 10,000,’ he said

The project hopes to create a road map for how to identify solar siblings, in preparation for the flood of data expected soon from surveys like Gaia. Pictured is the young star cluster NGC1818 taken as part of calibration and testing before the science phase of the Gaia telescope mission begins

'Don’t invest a lot of time in analyzing every detail in every star,' he said.

'You can concentrate on certain key chemical elements that are going to be very useful.'

These elements are ones that vary greatly among stars, which otherwise have very similar chemical compositions, and are largely dependent on where in the galaxy the star formed. Ramirez’s team has identified the elements barium and yttrium as particularly useful.

Once many more solar siblings have been identified, astronomers will be one step closer to knowing where and how the sun was formed. To reach that goal, the dynamics specialists will make models that run the orbits of all known solar siblings backward in time to find where they intersect: in other words, their birthplace.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Through this ever open gate

None come too early

None too late

Thanks for dropping in ... the PICs